“Tears, safety pins, rips all over the gaff, third rate tramp thing, that was purely really, lack of money. The arse of your pants falls out, you just use safety pins”

-Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols

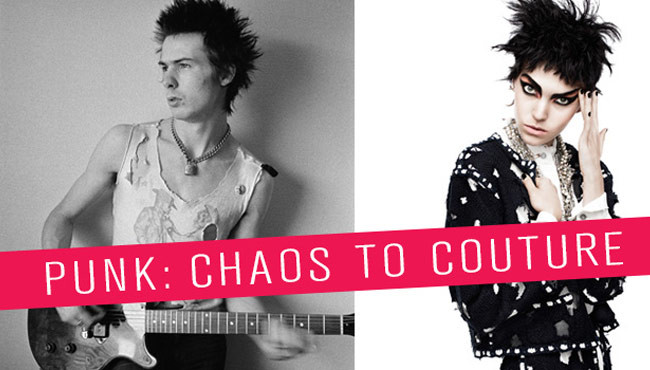

This quote sums up the origins of the punk era, taken from one at its center, Johnny Rotten. I copied it from one of the walls in the Punk: Chaos to Couture exhibit currently on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, here in New York City. It was located towards the end of the rather large collection. Copying it was difficult because the area it was located in was dark, crowded and full of flashing light thrown off of the massive video display on a nearby wall. I felt compelled to copy it because it allowed me to identify the feeling of “something’s just off…” that I was afflicted with while taking everything in.

Let me explain myself. Directly beneath this Johnny Rotten quote reads:

“More than any other aspect of the punk ethos of do-it-yourself, the practice of destroy or deconstruction has had the greatest and most enduring impact on fashion.”

It continues on for a bit. Espousing all of the ways that punk style, method, material and attitude has influenced many of the designer featured in the exhibit. What the composer of this spiel apparently misses, which I saw clearly with reading these things one after the other, is the huge irony of the entire exhibit. Mr. Rotten’s quote tells you directly, punks wore their clothes that way because they had no choice! This style/lifestyle grew organically. It grew out of necessity. And it became cool (and political) because those who rocked the style were so awesome, so talented, so in your face their lack of money and torn, pinned clothing only made them better, more interesting, more desirable. So, a ritzy museum like the MET, which calls one of the toniest neighborhoods in NYC home, offering an exhibit on the fashion of the poor, downtrodden and disenfranchised is really quite amazing.

Title Wall Gallery/Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

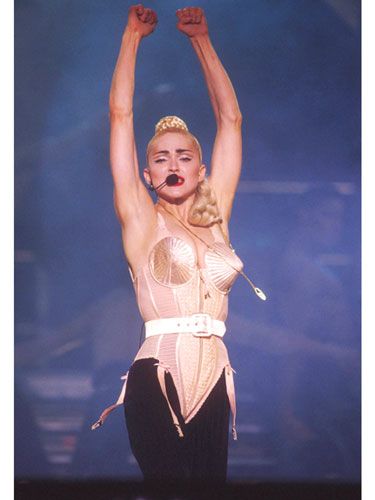

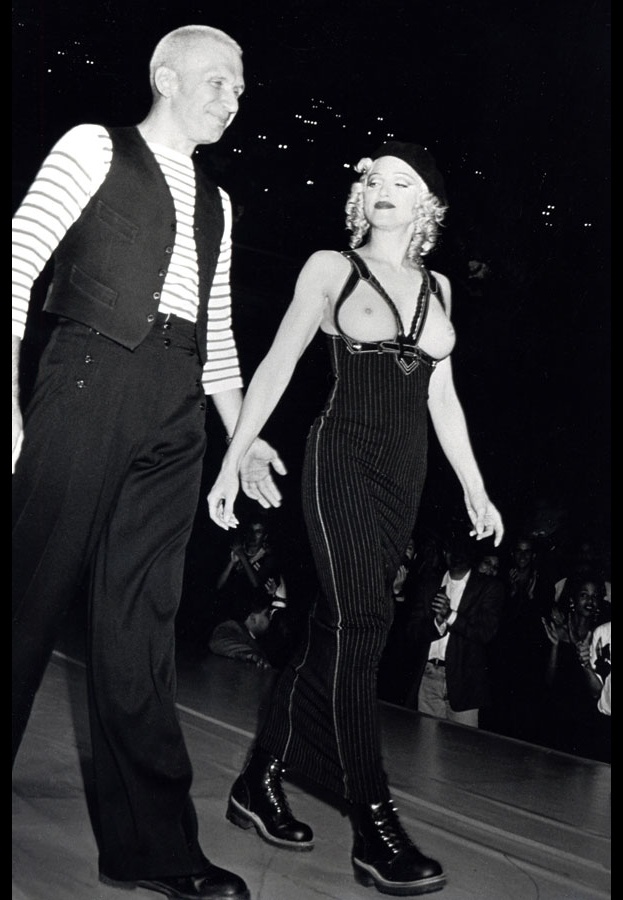

When you walk into the chamber that punk claimed you are met with a massive, jarring video display that is Right. In. Your. Face. It’s followed with a reproduction of the filthy bathroom at CBGB and continues with the actual clothes made/worn/sold by punks and punk Godmother Vivienne Westwood and her god-children the Sex Pistols. The moody dark atmosphere of it all the sets bar at a height that the remainder of the exhibit fails to meet.

Facsimile of CBGB bathroom, New York, 1975/Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

430 King’s Road Period Room/Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

D.I.Y.: Hardware/Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The above chamber does feature some vintage punk couture. However, from here on, many of the items featured are “punk inspired” designer clothes. Designer clothes that cost into the thousands of dollars. That is not punk. A neatly trimmed grocery store shopping bag paired with silk shantung pants does not make quite the same statement as safety pinning the ripped crotch of your pants together because you can’t afford to buy new ones. In my humble opinion. Strategically slashed designer jeans are not DIY. The do-it-yourself label cannot be applied to mass produced goods. Can it? Attaching two lengths of elastic to some black netting, and charging a fortune for it, is not a continuation of the punk era.

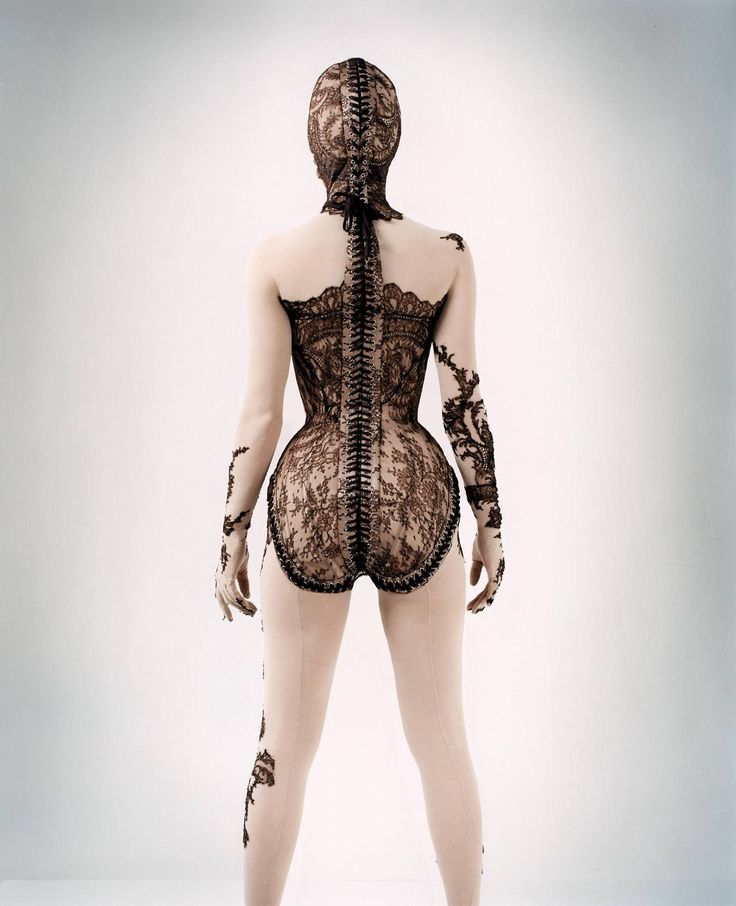

Don’t get me wrong. There are some absolutely stunning things in this collection. Particularly some additions by Alexander McQueen and this set of dresses made with hand painted fabric.

D.I.Y.: Graffiti & Agitprop/Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

But, unless Dolce and Gabanna painted and then wore these gowns themselves, can they really be DIY?

After you take in all of the color and slash and ironically contrary text spread around the place, you’re dumped out into a gift shop. A gift shop. Could they have ended on a less punk note? There is not one piece of free memorabilia for this collection. Well, if there was I surely did not see it. What you are given is the opportunity to spend $46 on a book about it. Or to buy a postcard with Sid Vicious scowling on it. Or a studded platform shoe key chain….

This photo, where I’m reflected in a sign pointing me toward the exhibit, is all I have to remember the experience by.

To visit Punk: Chaos to Couture online, click here.

This review originally appeared on Handmaker’s Factory.

Thanks to Nichola for making the arrangement for me!